Premalignant Cells Already Know How to Hide From the Immune System

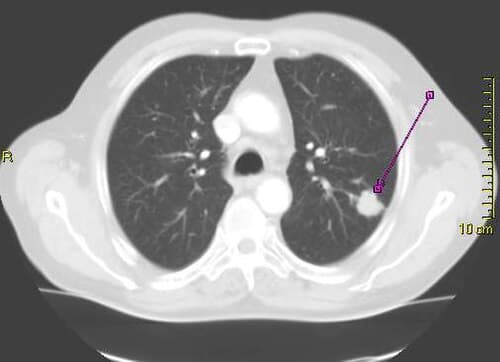

Long before a lung tumor becomes detectable on a scan, the cells that will eventually give rise to cancer are already engaged in a sophisticated arms race with the immune system. A new study has revealed the specific molecular mechanisms by which premalignant lung lesions evade immune detection, findings that could open the door to intercepting cancer at its earliest and most treatable stage.

The research, conducted by a multi-institutional team of oncologists and immunologists, analyzed tissue samples from patients with premalignant bronchial lesions, the kind of abnormal growths that sometimes progress to squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. While not all such lesions become cancerous, understanding why some do and others do not has been a central question in cancer prevention research for decades.

The Immune Escape Playbook

What the researchers found was striking: even at this very early stage, premalignant cells had already begun deploying immune evasion strategies that are typically associated with advanced, established tumors. The cells showed significant upregulation of immune checkpoint molecules, including PD-L1, along with alterations in the antigen presentation machinery that normally allows immune cells to recognize and destroy abnormal tissue.

Disrupting the Danger Signal

One of the most consequential findings involves the downregulation of major histocompatibility complex class I molecules on the surface of premalignant cells. These molecules serve as a kind of molecular identity badge, presenting fragments of internal proteins to patrolling T cells. When MHC-I expression is reduced, T cells effectively become blind to the abnormal cells, allowing them to proliferate unchecked.

The study also identified changes in the local immune microenvironment surrounding the lesions. Regulatory T cells, which normally function to prevent autoimmune reactions, were found in elevated numbers around premalignant tissue. These immunosuppressive cells appear to create a protective niche that shields emerging cancer cells from attack by cytotoxic T lymphocytes and natural killer cells.

Implications for Cancer Interception

The concept of cancer interception, intervening after the earliest molecular changes but before a clinically significant tumor develops, has gained considerable traction in oncology. However, interception strategies have been hampered by a limited understanding of what drives progression from premalignancy to full-blown cancer.

This research fills a critical gap by demonstrating that immune evasion is not merely a late-stage adaptation but a foundational capability that premalignant cells develop early. It suggests that the transition from precancer to cancer may be governed less by the accumulation of additional mutations and more by the success or failure of immune surveillance.

Could Immunotherapy Work Earlier?

One of the most exciting implications is the possibility of deploying immunotherapy drugs, currently the backbone of treatment for advanced lung cancer, at the premalignant stage. Checkpoint inhibitors such as pembrolizumab and nivolumab work by blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction that tumors exploit to evade T cells. If premalignant lesions are already using this same mechanism, early administration of checkpoint inhibitors could theoretically prevent cancer from ever developing.

Clinical trials exploring this approach are already being planned. However, researchers caution that the risk-benefit calculus is different for cancer prevention than for cancer treatment. Checkpoint inhibitors carry significant side effects, including autoimmune reactions, and administering them to patients who may never develop cancer requires careful patient selection and rigorous evidence of benefit.

Single-Cell Resolution Reveals Complexity

The study leveraged single-cell RNA sequencing to map the immune landscape of premalignant lesions with unprecedented resolution. This technology allowed researchers to identify not just the types of immune cells present but their functional states, revealing a complex ecosystem of activation, suppression, and exhaustion occurring simultaneously within a single lesion.

Among the most noteworthy findings was the presence of exhausted T cells in premalignant tissue. T cell exhaustion, a state of functional impairment caused by chronic antigen exposure, was previously thought to be a feature of established tumors. Its presence in precancerous lesions suggests that the immune system recognizes the threat early but is gradually worn down by the persistent presence of abnormal cells.

Mapping the Progression Pathway

By comparing lesions that progressed to cancer with those that regressed or remained stable, the team identified molecular signatures that distinguish dangerous lesions from benign ones. Lesions with stronger immune suppressive profiles and more extensive MHC-I downregulation were significantly more likely to progress, providing potential biomarkers for risk stratification.

This information could be invaluable for pulmonologists who monitor patients with known premalignant lesions, particularly former smokers who undergo regular bronchoscopic surveillance. Currently, the decision of whether to biopsy, ablate, or simply watch a suspicious lesion is guided largely by morphological criteria. Molecular profiling of the immune microenvironment could add a powerful new layer of information to guide these decisions.

A Paradigm Shift in How We Think About Cancer

The broader significance of this work extends beyond lung cancer. If immune evasion is a universal early event in carcinogenesis, similar mechanisms may be at work in premalignant lesions of the colon, breast, skin, and other organs. Research groups around the world are now investigating whether the findings can be generalized across cancer types.

For patients at high risk of lung cancer, the message is cautiously optimistic. While the discovery of immune evasion in precancerous tissue underscores the cunning of incipient cancer, it also reveals vulnerabilities that medicine may soon be equipped to exploit. The era of cancer interception, once a theoretical aspiration, is moving steadily closer to clinical reality.

As the researchers noted, understanding the enemy's playbook is the first step toward defeating it. By revealing how premalignant cells learn to hide, this study provides a roadmap for developing interventions that strip away their camouflage and allow the immune system to do what it was designed to do: eliminate threats before they cause harm.